The Joy of Creation

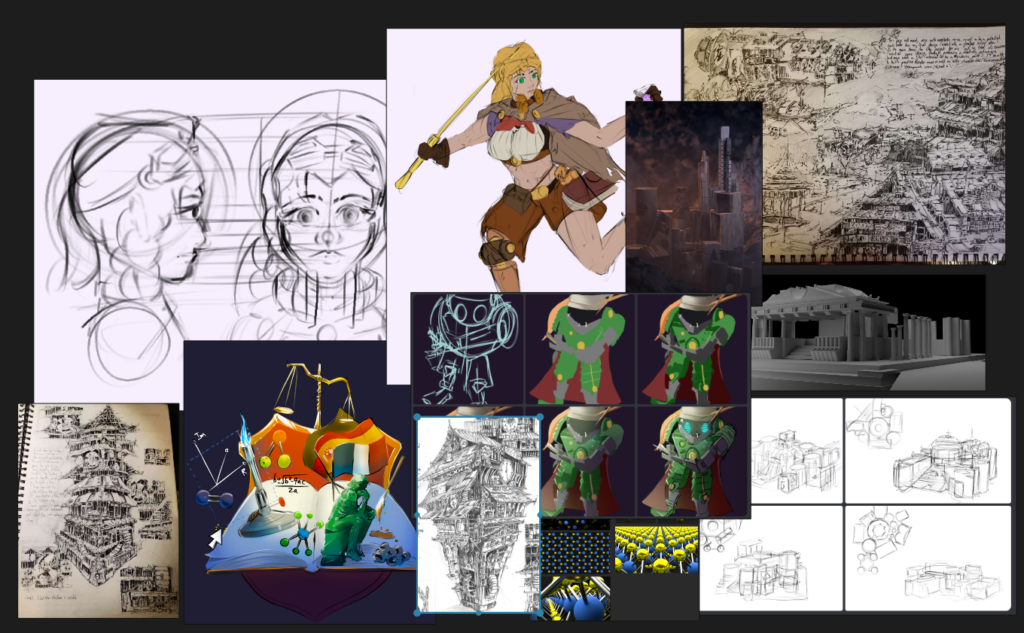

Really, I’m not really sure where I got the urge to choose fine art and graphics again for my A-levels. When friends ask me, I always find myself defaulting to that same old answer again: “Well, art and graphics aren’t actual subjects as, for me, I do passively them in my free time anyway…”, suggesting that my personal work from outside of school would all culminate in this gigantic portfolio by the end of sixth form.

Truthfully, the bleak reality stands that those external projects probably weren’t going to make it anywhere near my school portfolios, whether that be as a result of being unable to cohesively link it in with anything ongoing at school or because I subconsciously think that sliding it into my stinky portfolio would somehow devalue that project.

The real reason as to why I picked those subjects again lies alongside no romantic reason. I didn’t find myself ready to brandish a paintbrush the day I was born; nor was I ‘talented’ or passionate enough to justify subjecting myself to two coursework behemoths again at A-Level. Out of the two professions I wanted to work for, game design and architecture, you never strictly needed both fine art and 3D design to get into undergrad courses; only ever one or the other.

In fact, maybe mistakenly, I think that universities would much prefer physics as one of the subject options, so I could’ve easily dropped either in exchange. I forsook a chance to maybe score a higher likelihood of getting into a good university; to further explore my academic potential!

I had picked the subjects out of FEAR HUBRIS STRESS ; not for the Joy of Creation

Fear that in those academically competitive courses, I’d never be able to come out on top, fear that I would find those subjects mundane as I did during the GCSEs, and of once again eventually facing, again, the insurmountable stress that prevailed over revision periods.

Means of escape, however, tend never to result in liberation- you’re only ever hiding from inevitable disappointments or from unforeseen consequences. I realised this sometime through the third term after dropping physics. All of my friends and acquaintances that I surrounded myself with at school just seemed to know so much more about the world than I do, whether that be from quantum physics to tax evasion; Immanuel Kant to Otto von Bismarck.

In search of freedom from academic pressure, I found myself completely dropping out that race; to later receive a seething cramp, barring me from re-entering after seeing my peers lap me both in intellect and street-wiseness, again and again.

Sure, you might not be the most academic individual & might not be the most street-wise either, in stalwart pursuit of the visual arts; you must remember that these things take time and maybe serendipity to develop.

The arts don’t expedite you to becoming a technical genius but they certainly don’t bar you either. I’ve often viewed it as a ‘haptic’ method to foster that kind of knowledge: something that, whilst slow in process, leads you on a more physically rewarding path, one which also branches to a myriad of possibilities, in contrast to pure devotion to academic papers, textbooks, lectures or literary classics that you might imagine technical students engage with.

Of course, this isn’t a critique of any sort on STEM subjects; just reassurance for people who think that, because they chose a purely creative path, it doesn’t mean that you’re beneath anyone else working in any other field, something that I myself subconsciously believe to this day.

Luckily, for me, at that point it wasn’t too big a problem as it would’ve been at the beginning of the year. I’d finally found myself becoming increasingly passionate about my creative endeavors, being able to dish out time that, otherwise, I would’ve been combing through textbooks, to pursue the momentary tranquility that came with pencil and paper. Of course, school coursework somehow always ends up irking and demotivating me in some way, and usually because I started off on the wrong footing. “I want to produce a heavily technical architectural project!”, I say, “I’ll produce 20 pages in 2 weeks”, I say.

Yeah, that never worked out; probably never will in secondary school.

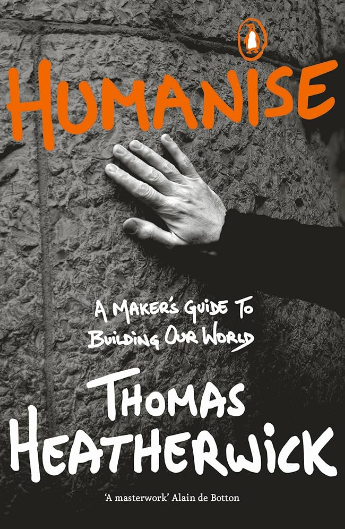

On a side note, I’ve recently been reading Thomas Heatherwick’s ‘Humanise’ as a piece of preparation for architectural interviews in the not-so-distant future & I think that it definitely helped me reaffirm my commitment to the creative industry.

The ability that architecture has to determine cortisol regulation, community cohesivity, physical health & individual freedom as an essential fine art baffles me. The book helped me better understand that, at least during architectural design, bogging yourself down in technicalities and efficiency might actually be detrimental to consumer welfare, in contrast to designing buildings with a main focus on beauty through purely detailed forms.

Sure, your average skyscraper might be spacious thanks to its concrete core, quiet and easily maintainable courtesy of its drop ceilings, sleek and bright with employment of curtain walls; those very features result in a lack 3 dimensionality, detail, and psychological stimulation.

A good architect for our epoch must strip themselves of affiliation with the industrialised, so-called ‘efficient’ building production schemes of erstwhile internationalists, who fetishized the idea of a systematic, standardised &, potentially, dystopian future. They must not be ashamed to go back to the stimulating aesthetics of the Beaux-Arts school in fear of appearing out of touch with ‘modernity’, or scientifically challenged, as I was (and, to a degree, still am).

Architecture has, since the dawn of time, been in a race alongside technological advancement; sometimes, for the benefit of a greater proportion of people’s mental wellbeing, I think it’s best if it were to look back at time periods similar to our current one and reset our foundations at schools and practices, than stubbornly pursuing a failed modernist, technocratic dream.

Honestly, I probably should apply some of the words said here to my perspective on academics…

It’s really an awesome book that offers a popular, yet somehow underappreciated perspective on modern architecture that I recommend you check out if you often find yourself frustrated with our contemporary urban fabric.

Check it out here!