‘Place is where the mind touches the world, defined by architecture, acting as syntax for the story of life’

Due to my interest in the creative arts and the sciences, I’ve always wanted to study architecture from a young age (I know, cliched point but c’mon most people are programmed like this). I used to think that the subject’s history was probably pretty bleak, possibly attributing to its the general consensus that its human constituents are usually hubris-ridden, white-collared pillocks. Through delving deeper into architectural history, however, & upon developing an interest in ‘archiculture’, I’ve come to the realization that it is anything but. As a rich melting pot of all different branches of specialism, architecture is really but the Smithfield’s of careers- a vibrant community where its intrinsic parts all play a pivotal role of worldbuilding, both literally and metaphorically.

I don’t think a career as diverse as this wouldn’t have much (at least, cohesive) longevity when little, if any, notable records are written on it, which is why I’ve also come to respect architectural historical documents. Their playing a part in safeguarding information keeps the profession of interest to future generations via continuing to facilitate the idea that architecture is everyman’s career- forever guiding a steady flow of new talents forward through times of great paradigm shifts.

I’m writing this article to contribute my own bit of architectural memorabilia toward the perpetuation of this keystone career.

Let us start from the beginning of the end.

Really, by the end of the 20th century and the advent of extreme technological advancement, ‘architecture’ as a concept had lost its meaning. Sir Gilbert Scott put it nicely during the 19th century as a profession that ‘makes functional buildings beautiful’, but this frivolous façade gradually became frowned upon by technocratic masters the likes of Le Corbusier. For instance, Mies Van Der Rohe, a prominent German American architect, pioneered the development of the so-called ‘international’ style, producing timeless domestic masterpieces in likes of the Villa Tugendhat or the Barcelona pavilion.

When you think of modernism, the first things that spring into your mind are probably those sleek, geometric Hollywood houses with their magnificently white, cantilevered roofs, rich mahogany brise-soleil and delicate curtain walls. Technically, that kind of style can only be seen as a relative or offspring of the central ‘modernist’ movement, a ‘contemporary’ reimagination of a functionalist epidemic which persisted trough much of the early 20th century.

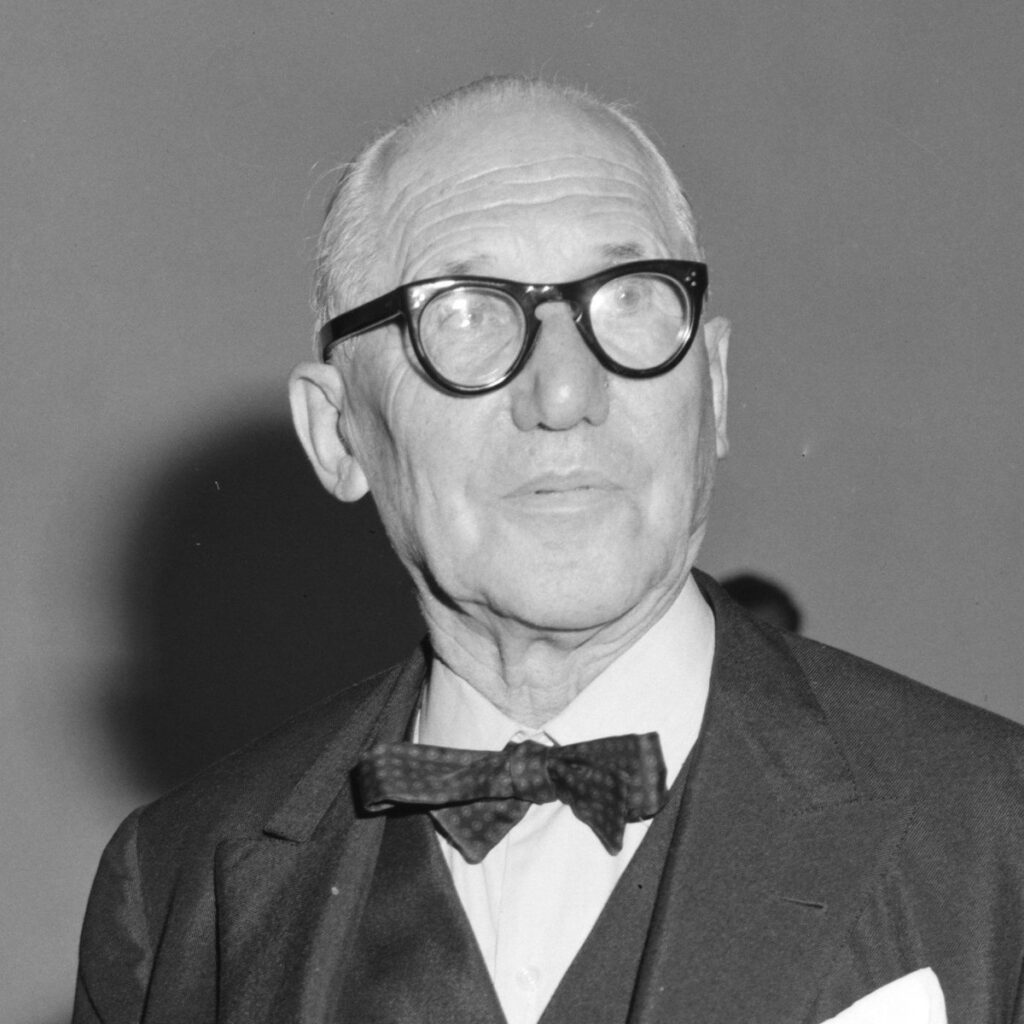

In truth, the ‘modernist’ style was something born out of necessity and a yearn for change, a ‘democratic’ building concept which would reshape how we constructed our homes, neighborhoods and cities to accommodate an increasing worker population. Throughout much of this period, the illusive Le Corbusier dominated the architectural scene, a narcissistic genius (or insane megalomaniac, depending on how you want to see it), puppeteering it for selfish gain behind a veneer which spoke of a utopian urban fabric. From his perspective, architecture of the past reflected an outdated, frivolous charade, too far removed from the stoic and functionalist classical period and too exclusive for the working class.

At the heart of all this, Le Corbusier believed that the problem lied within its practitioners, who were too busy complicating building forms as if working on sculptural masterpieces to turn an eye to the real problems plaguing their society, be it with the housing crisis following the great depression, the homeless epidemic which ravaged urban streets or the growing number of favellas and slums just on the outskirts of a rotting city. The ethics of past architects wouldn’t have had a place in new institutions like the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris or the Engineering Academy of Dresden, & conversely, Le Corb marveled at the development and streamlining of the industrial process taking place during this time of technological innovation. He revered the engineers who created machines and inspired new workflows, making what was originally exclusive to the rich, accessible for society at large. Often, he would distain at the stagnancy of architecture, and how it failed to incorporate itself into the technological revolution: how can such a keystone subject which humans have been dependent on for thousands of years to survive, now be so resistant to changes around the society that it helped accommodate?

The truth was that architecture needed a guiding light and some crutch to lean on in its old age, and functionalist, streamlined industrial processes of the new technological era provided that illusive opportunity.

‘’Our architects are disillusioned and unemployed, boastful or peevish. This is because there will soon be nothing more for them to do. We no longer have the money to erect historical souvenirs. At the same time, everyone needs to wash! Our engineers provide for these things and so they will be our builders.’’

-Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture

So came a new era for architecture, pioneered by Le Corbusier and the likes, a functionalist version pulled together using the strings of industrial efficiency. It was from these foundations that bloomed the most influential society in Architectural history- CIAM (Congres Internationale d’Architecture Moderne), an exclusive member’s club consisting of architectural magnates the likes of Gropius, de Silva, Aalto and van Eesteren. This society founded the core principles of modernist architecture via the la Sarraz declaration of 1928, declaring that architecture cannot exist without intrinsic links with politics and economics, reestablishing its position as more of a social science than a fine art, substantiating its usefulness in a modern setting. Among its most prolific contributions to the built environment, two period-defining principles and publications stood out the most, being the idea of ‘Existenzminimum’ (or ‘subsistence dwelling’) and the Athens Charter.

The problem of architecture’s limited accessibility to the less fortunate of society was brought to the foreground via discussions at CIAM 2 in ’22, where an attempt to curtail this conundrum was drummed up in the form of minimum housing requirements. These building standards outlined the most basic framework of a human dwelling, based on three requirements alluding to Le Corbusier’s personal building philosophy, declaring -respectively- that the house needed to be a ‘receptacle for light’, a ‘shelter from the elements’ and ‘have distinct cells for different functions’. By breaking the concept of domestic housing down to its most constituent forms, CIAM was able to gain foundational data which will contribute to the eventual mass-production of housing units befit the booming working population.

This ambition was eventually realised through the medium of ‘zeilenbau rows’ following discussions on possible implementation of these building standards on a larger, neighbourhood-wide scale in CIAM 3. Initially, circular perimeter blocs were suggested as a possible candidate for new modernist communities; following further deliberation it was decided that this was in violation of the sunlight receptacle principle previously stated during their second meeting, therefore linear rows of economically beneficial concrete housing blocs were instead settled upon, as they provided maximum sunlight gain for minimal building footprint. As a result, mass-production of these housing units was able to begin across much of Europe to facilitate the furthering industrialisation of major cities, finally providing the housing that workers deserved & outlined these subsistence dwelling principles as basic human rights, which, ultimately, is objectively, a good thing. This sort of wholistic, practical discussion between star architects (or even among most other professions) was few and far between just a few decades before, and I believe that it marks a significant point for building research in architecture at a level which we periodically struggled to reproduce after the formal dissolution of CIAM in 1959.

Following these discussions came the most important meeting in CIAM, and potentially, architectural history, culminating in the form of a small book aptly named the Athens Charter, as it found itself orchestrated on a little cruise ship on its way to Greece.

Before this, CIAM had been working up from a microcosmic, single house level in the form of Existenzminimum to zeilenbau town planning, all culminating towards CIAM’s attention to something more pressing for future urban development in the form of the ‘functionalist city’. Following the study of 34 existing cities, a basic framework for the urban modus operandum was erected around its core programs of ‘recreation’, ‘housing, ‘transport’ and ‘working’. It was here where the now infamous monofunctional zoning crept up, whereby cities would be divided into their respective zones via hard edges, usually demarcated by highways or other transport routes. With the development of automobile technology, the CIAM leading board (made out of arguably arbitrary people who weren’t necessarily voted in, but had the most influence nonetheless) argued for increased prevalence of motor infrastructure around these different zones, efficient enough so that one can reach from their workplace, to the local park and back home in no less than an hour, under a principle named the ‘one hour city’ devised by the Dutch urban planner, van Eesteren, the erstwhile head of committee.

Read more about CIAM IV’s mishaps here

Until today, only two cities have been constructed purely on the city, town and housing planning principles of CIAM, being in Brazil and the newly independent India, respectively Brasilia and Chandigarh. Perhaps, among these two, Chandigarh offers a better presentation of modernist ideals. This is reflected in first and foremost the city’s urban plan, directed by none other than Le Corb himself. The fulcrum of which the general urban framework was laid out presented itself metaphorically as a human body. The ‘head’ of the body would home the general secretariat and court alongside various parliamentary complexes, and the so-called ‘circulation system’ would find itself realised as an interconnected grid of roads bridging from the ‘7 V’s’, or the regional highway system. The analogised ‘lungs’ would be presented as a series of green corridors which spanned parallel lines from North to South, and the ‘heart’ of the city pulsates in district 17, where visitors would stumble upon the commercial, cultural and transport centre which facilitate the city’s recreational aspirations. At the microcosmic level, each house was constructed from meticulous use of bare-bone, durable materials such as unpainted, unplastered brick in an attempt to minimise costs in compensation for a limited budget set at (what is in modern day) $500M, barely enough to make a pair of skyscrapers. Each of these bricks also encouraged passive ventilation via pores which facilitate the creation of convectional currents.

Unfortunately, in the modern day, these urban principles are only remembered for their errors, of which possibly outnumber their benefits, as you may have been able to deduce from the previous Farnsworth section. Individuals like Le Corbusier were far from perfect, or even ‘good’ people, as their love for architecture came in pairs with this desire to wield total, authoritarian control over our built environment. They had the ability to do so, too, as architecture is such a niche, important yet, relative to them, in their time period, uncompetitive subject. Failed megaprojects/concepts such as the Plan Voisin, Bijlmer district or Hilberseimer’s plan for Chicago only serve as reasons to dislike the modernist movement for its fetishisation dystopian or even potentially communist ideas. As for existing cities and buildings influenced by this period, modernism seems to only have had negative impacts, be it with the hierarchical segregation it promotes in cities the likes of Caracas or the counterproductive and undemocratic construction of Brasilia, heightening the social divide whilst also being unable to provide ‘beautiful’ feats of construction, in a step down from even baroque architecture.

However, I would like to post the argument here that modernism was once, at its core, a positive movement. Similar to what Le Corbusier believed, I think the problems with modernist philosophies exist due to its intrinsic connections with morally questionable figures as opposed what the philosophies actually dictate. Architecture only exists in accordance to the context it is informed by &, case in point for the modernists, their movement came about primarily due to the economic, political and technological upheavals brought about by the 20th century. If those boring apartment blocks were not created, those minimum housing requirements were never outlined and strict zoning laws were never put into effect, then workers would have nowhere to cheaply reside, social housing which do exist would only do so at an informal level and industry plants would sprawl endlessly throughout what’re meant to be peaceful neighbourhoods.

Modernism became tarnished as a movement primarily because of architectural stagnation in the late 20th century. The time of which it found itself in was no longer that period of great financial turmoil, where factories but not skyscrapers dominated the skyline. Now, the world had moved on, turning into a capitalist, monetary greenhouse where a privileged few have control over much of Earth’s resources. Architecture was once again left behind societal progress, trapped in that modernist principles &, as a consequence, was exploited by newly established tycoons and magnates, facilitating the construction of drab, ugly concrete parking blocks, underutilized green spaces and sprawling suburbia. In ‘The Architecture of Happiness’, I went over an entry created by Alain de Botton in regard to idealistic architecture, often presenting themselves in churches, governmental buildings, private manors or exclusive intellectual clubs such as the Athenaeum. Often, the unethical individuals or ideologies which these neoclassical structures harbour contradict the utopia the buildings physically preach; does that mean we should stand against those utopian ideals?

Anyhow, the point still stands that what our society needs now are promising young architects and urban planners who have the innovative prowess to drive us away from these outdated principles. Let it be known, however, that instead of completely tearing down modernist values, we should build on them and accommodate them for contemporary existence. New architects must find that intermediary zone between revering modernists (which would only ever prolong architectural stagnation) and detesting their principles whilst starting from the drawing board, for that is now the only way for architecture to catch up with our new millennium.